Authored by Emeli Dral and Elena Samuylova, creators of Evidently (GitHub), an open-source ML and LLM evaluation framework with 25M+ downloads.

This is the third of five chapters.

Together with this theoretical introduction, you can explore a practical Python example on different LLM evaluation methods.

Deterministic evaluations

Now, let’s take a look at the different methods you can use to evaluate generative outputs — starting with deterministic evaluation methods that are rule-based and directly computable.

These simple methods matter. Evaluating generative systems doesn’t always require complex algorithms: simple metrics based on text statistics and structural patterns can often offer valuable insights. They are also generally fast and cheap to compute.

Text statistics

Text statistics are numerical descriptive metrics that capture properties of the generated output — such as its length. They are reference-free, meaning they can be computed without needing a ground truth response. This makes them useful for lightweight monitoring in production.

Text Length

What it checks. Measures the length of the generated text using:

- Tokens

- Characters (symbols)

- Sentence count

- Word count

When it is useful. This is useful for tasks like content generation (especially when length constraints exist) or summarization, where excessively short or long outputs may indicate problems. For instance, too short responses may lack fluency, while overly long ones may include hallucinations or irrelevant content.

Verifying text length is also relevant in applications like Q&A systems or in-product text generation, where display space is constrained. Instructions about the desired length of a response are often included in the prompt — for example, you may be asking the system to “answer in 2–3 sentences.” You can use text length metrics to verify whether the output aligns with the prompt’s expectations.

Example

“Your meeting with the product team is confirmed for Thursday at 2 PM. Let me know if you’d like to reschedule.”

Character length: 102 (including spaces and punctuation), word count: 18, sentence count: 2

How it’s measured

- Character count: straightforward string length.

- Word/sentence counts: split on whitespace or punctuation, or use tokenizers (e.g., NLTK, SpaCy).

Out-of-Vocabulary Words (OOV)

What it checks. Calculates the percentage of words not found in a predefined vocabulary (e.g., standard English vocab from NLTK).

When it is useful. This can flag misspellings, nonsense outputs, or unexpected language use. For example, high OOV rates may suggest:

- Poor decoding quality

- Spammy or obfuscated content (e.g., in adversarial inputs)

- Unexpected language use in applications expecting English-only responses

Example

“Xylofoo is a grfytpl.” → High OOV rate flags made-up words

How it’s measured. You can import vocabularies from tools like NLTK.

\[\text{OOV Rate} = \left( \frac{\text{Number of OOV Words}}{\text{Total Words}} \right) \times 100\]Non-letter character percentage

What it checks. Calculates the percentage of non-letter characters (e.g., numbers, punctuation, symbols) in the text.

When it is useful. for spotting unnatural output, spam-like formatting, or unexpected formats like HTML or code snippets.

Example

“Welcome!!! Visit @website_123” → High non-letter ratio

How it’s measured.

\[\text{Non-Letter Percentage} = \left( \frac{\text{Non-Letter Characters}}{\text{Total Characters}} \right) \times 100\]Presence of specific words or phrases

What it checks. Whether the generated text includes (or avoids) specific terms — such as brand names, competitor mentions, or required keywords.

When it’s useful.This helps you verify that outputs:

- Stay on-topic

- Avoid inappropriate or banned terms

- Include required language for specific tasks (e.g., legal disclaimers)

Example: For a financial assistant, you may check whether outputs include required disclaimers like “this does not constitute financial advice.” Similarly, for a healthcare chatbot, you might verify the presence of phrases such as “consult a licensed medical professional” to ensure safety and compliance.

How it’s measured. Use a predefined list of words or phrases and scan the generated text for TRUE/FALSE matches.

Pattern following

Pattern-based evaluation focuses on the structural, syntactic, or functional correctness of generated outputs. It evaluates how well the text adheres to predefined formats or rules — such as valid JSON, code snippets, or specific string patterns.

This is useful both in offline experiments and in live production, where it can also act as a guardrail. For example, if you expect a model to generate a properly formatted JSON and it fails to do so, you can catch this and ask to re-generate the output. You can also use these checks during model experiments — for example, to compare how well different models generate valid structured outputs.

RegExp (Regular Expression) matching

What it checks. Whether the text matches a predefined pattern.

When it’s useful. For enforcing format-specific rules such as email addresses, phone numbers, ID or date formats. It ensures that the output adheres to predefined patterns

Example

Pattern:^\(\d{3}\) \d{3}-\d{4}$

Valid match:(123) 456-7890

How it’s measured. Use a regular expression with libraries like Python’s re module to detect pattern matches.

Check for a valid JSON

What it checks. Whether the output is syntactically valid JSON.

When it’s useful. This is important when the output needs to be parsed as structured data — for example, passing the response to an API, writing to configuration files, storing in a structured format (e.g., logs, databases).

Example

✅{"name": "Alice", "age": 25}

❌{"name": "Alice", "age":}

How it’s measured. Use a JSON parser such as Python’s json.loads() to check if the output can be parsed successfully.

Contains Link

What it checks. Whether the generated text contains at least one valid URL.

When it’s useful. To verify that a link is present when you expect it to, in outputs like emails, chatbot replies, or content generation.

Example

✅ “Visit us at https://example.com” ❌ “Visit us at example[dot]com”

How it’s measured. Use regular expressions or URL validation libraries (e.g., validators in Python) to confirm URL presence and format.

JSON schema match

What it checks. Whether a JSON object in the output matches a predefined schema.

When it’s useful. Whenever you deal with structured generation and instruct an LLM to return the output of a specific format. This helps verify that JSON outputs not only follow syntax rules but also match the expected structure, including required fields and value types.

Schema example

{"name": "string", "age": "integer"}✅ Matches:

{"name": "Alice", "age": 25}

❌ Doesn’t match:{"name": "Alice", "age": "twenty-five"}

How it’s measured. use tools like Python’s jsonschema for structural validation.

JSON match

What it checks. Whether a JSON object matches an expected reference JSON.

When it’s useful. In reference-based (offline) evaluations, where the model is expected to produce structured outputs. For example, in tasks like entity extraction, you may want to verify that all required entities are correctly extracted from the input text — compared to a known reference JSON with correct entities.

How it’s measured. First, check that the output is valid JSON and schema matches. Then, compare the content of the fields, regardless of order, to determine if the output semantically matches the reference.

Check for a valid SQL

What it checks. Whether the generated text is a syntactically valid SQL query.

When it’s useful In SQL generation tasks.

Example

✅SELECT * FROM users WHERE age > 18;

❌SELECT FROM users WHERE age > 18

How it’s measured. Use SQL parsers like sqlparse, or attempt query execution in a sandbox environment.

Check for a valid Python

What it checks. Whether the output is syntactically valid Python code.

When it’s useful. In tasks where generative models produce executable code. Ensures output can be parsed and run without syntax errors.

Example

✅def add(a, b): return a + b❌

def add(a, b): return a +

How it’s measured. Use Python’s built-in modules (e.g., ast.parse()) to attempt parsing. If a SyntaxError is raised, the code is invalid.

Pattern-based evaluators like these help validate whether generative outputs align with specific formats or functional requirements. They are especially useful in scenarios where the output must be used directly in applications like APIs, data pipelines, or code execution environments.

Overlap-based metrics

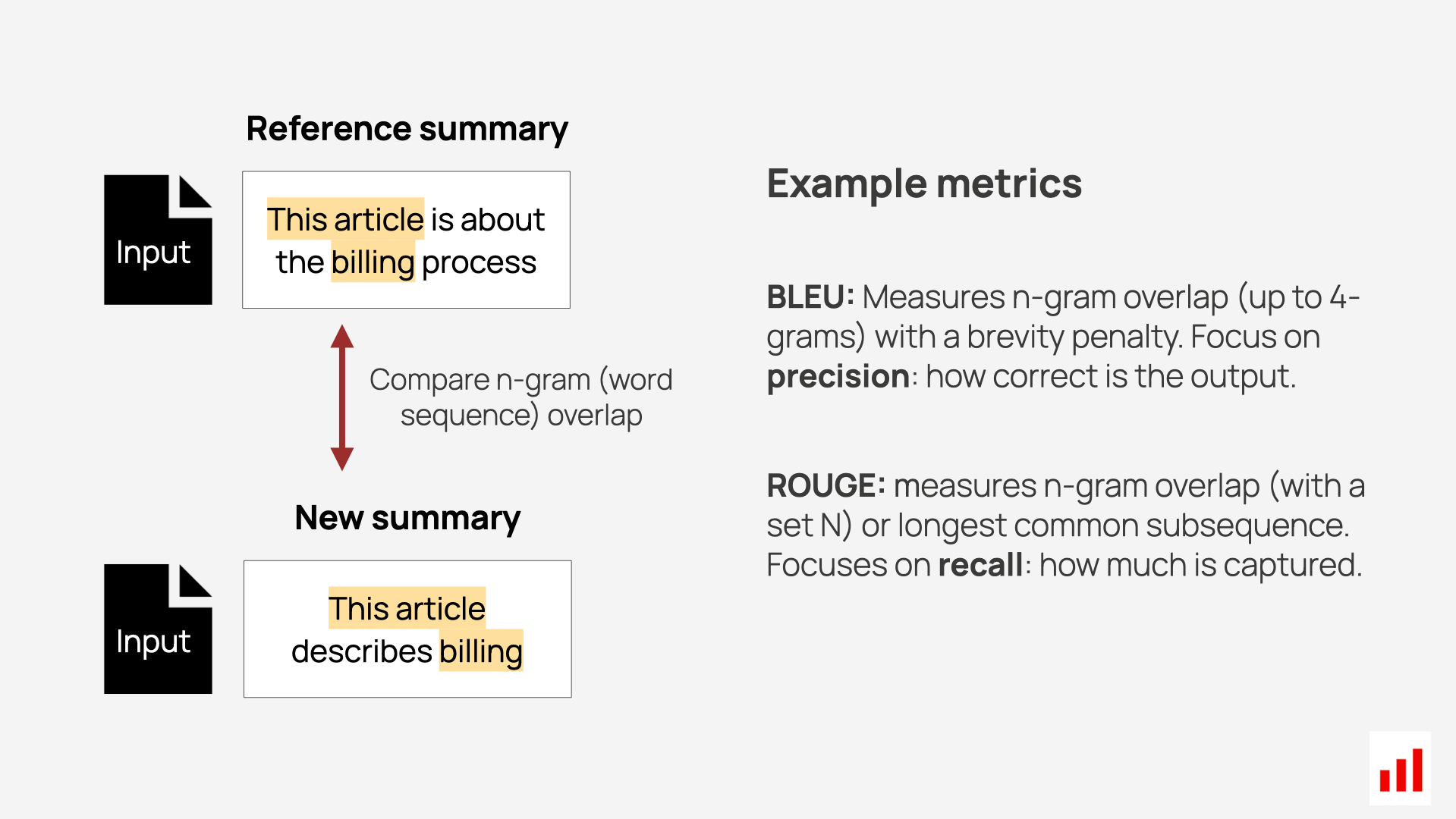

Compared to text statistics or pattern checks, overlap-based metrics are reference-based evaluation methods. They assess the correctness of generated text by comparing it to a ground truth reference, typically using word or phrase overlap.

Just like in predictive systems, you can evaluate generative outputs against a reference. But while predictive tasks often have a single correct label (e.g., “spam” or “not spam”), generative tasks involve free-form text, where many outputs can be valid — even if they don’t exactly match the reference.

For example, in summarization, you might compare a generated summary to a human-written one. But two summaries can express the same core content in different ways — so full-string matches aren’t enough.

To handle this, the machine learning community developed overlap-based metrics like BLEU and ROUGE. These measure how much the generated text shares in common with the reference — based on words, n-grams, or phrase order.

BLEU (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy)

What it measures. BLEU evaluates how closely a system’s output matches a reference by comparing overlapping word sequences, called n-grams (e.g., unigrams, bigrams, trigrams). It computes precision scores for each n-gram size — the percentage of generated n-grams that appear in the reference. It also includes a brevity penalty to prevent models from gaming the score by generating very short outputs.

This combination of n-gram precision and brevity adjustment makes BLEU a widely used metric for evaluating text generation tasks like translation or summarization.

Example

Reference: “The fluffy cat sat on a warm rug.”

Generated: “The fluffy cat rested lazily on a warm mat.”

- Overlapping unigrams (words): “The”, “fluffy”, “cat”, “on”, “a”, “warm” → 6/9 → unigram precision = 2/3

- Overlapping bigrams: “The fluffy”, “fluffy cat”, “on a”, “a warm” → 4/8 → bigram precision = 0.5

- Overlapping trigrams: “The fluffy cat”, “on a warm” → 2/7 → trigram precision = 2/7

- No overlapping 4-grams

- Brevity penalty is not applied here because the generated text is longer than the reference.

Final BLEU score:

\[\text{BLEU} = \mathrm{brevity\_penalty} \cdot \exp\left( \sum_n \mathrm{precision\_score}(n\text{-grams}) \right)\]

Limitations. While BLEU is a popular metric, it has some notable limitations.

- First, it relies on exact word matching, which means it penalizes valid synonyms or paraphrases. For example, it would score “The dog barked” differently from “The puppy barked,” even though they mean similar things.

- Additionally, BLEU ignores sentence structure and semantic meaning, focusing only on word overlap. This can lead to misleading results when evaluating the overall quality or coherence of text.

- Finally, BLEU works best for short, task-specific texts like translations, where there’s a clear reference to compare against. However, it struggles with open-ended generative outputs, such as creative writing or dialogue, where multiple different valid responses might exist.

ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation)

What it measures. ROUGE evaluates how well a generated text captures the content of a reference text. It is recall-oriented, focusing on how much of the reference appears in the output — making it especially useful for tasks like summarization, where the goal is to retain the key points of a larger document.

ROUGE typically includes two variants:

- ROUGE-N: Measures overlap of word n-grams (e.g., unigrams, bigrams) between the reference and the generated output. For example, it might compare single words (unigrams), pairs of words (bigrams), or longer sequences.

- ROUGE-L: Measures the Longest Common Subsequence (LCS) — identifying the longest ordered set of words shared by both texts. This captures structural similarity and sentence-level alignment better than simple n-grams.

Example

- Reference: “The movie was exciting and full of twists.”

- Generated: “The movie was full of exciting twists.”

- ROUGE-L would identify the Longest Common Subsequence (LCS) — the overlapping phrase structure shown in bold.

Limitations. Like BLEU, ROUGE has important limitations:

- It relies on surface-level word matching, and does not recognize semantic similarity — for example, it may penalize “churn went down” vs. “churn decreased” even though they are equivalent.

- It performs best when the reference output is clearly defined and complete, such as in extractive summarization.

- ROUGE is less effective for open-ended tasks — like creative writing, dialogue, or multiple-reference summarization — where the same idea can be expressed in many valid ways.

Beyond BLEU and ROUGE

While BLEU and ROUGE are useful for structured tasks like translation or summarization, they often fail to capture deeper qualities such as semantic meaning, fluency, coherence, and creativity.

This has led to the development of more advanced alternatives:

- METEOR: Incorporates synonyms, stemming, and word order alignment to better compare generated and reference texts. It improves on BLEU by being more forgiving of paraphrasing and word variation.

- Embedding-based metrics (e.g., BERTScore): Use contextual embeddings to measure the semantic similarity between the generated output and the reference. These models move beyond surface-level overlap, making them more robust for evaluating meaning.

In the next chapter, we’ll explore model-based evaluation — from using embedding models to assess semantic similarity, to applying ML models that directly score the outputs.

Let’s keep building your evaluation toolkit!