What hallucinations are and why are they important?

Language models sometimes generate text that is nonsensical or unrelated to the input, this phenomenon is known as hallucination Hallucinations survey 2022. For instance, 15–20% of ChatGPT responses were classified as hallucinations in 2023. A somewhat famous example of the hallucination by ChatGPT can be seen below:

This is a clear hallucination as Titanic disaster had more than 700 survivors with Charles Joughin being the last survivor to leave the Titanic rather than the sole survivor.

Although the mistake in the provided example might not seem so crucial, hallucinations in natural language generation are a significant issue. They reduce performance and raise safety concerns for real-world applications. In medical contexts, a hallucinatory summary from patient information could endanger the patient. Incorrect instructions for medicines generated through machine translation may cause life-threatening incidents. Hallucination may also lead to privacy breaches. It was showed that language models can be prompted to recover sensitive personal data from the training corpus, such as email addresses, phone numbers, and physical addresses. In addition, hallucinations are already causing problems in the legal industry. A lawyer in the US is awaiting a sanctions hearing for presenting hallucinated case law in court.

RALMs don’t save from hallucinations

Retrieval Augmented Language Models (RALMs) are designed to reduce the risk of hallucination caused by limited internal knowledge via incorporating large external knowledge bases during inference and equipping language models with up-to-date information. Despite this, RALMs can still produce hallucinations Failure modes of RAG, Hallucinations survey 2023.

Issues during context retrieval

Hallucinations in language models can stem from various issues during the retrieval process:

- Users may formulate ill-posed queries, see Self-RAG.

- External documents sources can contain contaminated information, see Contaminated data for RAG.

- Because of imperfect chunking (On retrieval granularity) or embedding (Better embeddings) retrievers may select irrelevant documents, which introduces inaccuracies into the generated output.

- Even when the retrieved context is accurate, irrelevant noise within the documents can negatively affect the results, see Noisy context.

- Additionally, when the retrieved context contains excessive redundant information, models may fail to focus on critical details. This is especially problematic with long texts, where LLMs are known to skip the information in the middle of the context, see Lost in the middle.

Issues during context utilization

Even when the retrieved context is ideal, such as manually retrieved and verified for accuracy, RALMs can still produce hallucinations. This occurs because the model may misread the context and make predictions that partially or fully disregard it.

We define information learned by model during pre-training as parametric knowledge and information extracted from retrieved documents during inference as contextual knowledge. It has been shown that hallucinations in RALMs become more pronounced when parametric and contextual knowledge conflict with each other Parametric answer in context, ClashEval.

The figure below shows an example of such a conflict. Without context, the model gives the answer “Malaria” (in red). We call such answers parametric answers because they rely only on parametric knowledge. When provided with context, the model should change its answer to “Cholera” (in green), which is correct.

In such a case misreading an accurate context leads to model falling back to its incorrect or outdated parametric knowledge and, therefore, hallucinating. We believe that this scenario is an important source of RALM hallucinations and will now examine it in more details.

RALMs misread context under knowledge conflict

As we have discussed in the previous paragraph, misreading context during conflicts between parametric and contextual knowledge causes RALM hallucinations. This issue must be addressed carefully, as knowledge conflicts often occur in the key RALM application scenarios. These scenarios include:

- Outdated pre-training data: pre-training a large language model takes months. During this time, factual information can become outdated.

- Lack of key knowledge in pre-training data: most end users do not train models from scratch in the current transfer learning paradigm. Instead, they adapt a few pre-trained models to downstream tasks through fine-tuning, prompting, or retrieval augmentation. These tasks are diverse and often need factual knowledge not present in the pre-training data.

- Noisy pre-training data: language models are pre-trained on large-scale text corpora, which may include unreliable information.

Examples of misread contexts

Model hallucinations often occur during conflicts. For example, it is known that slightly modifying the context can influence whether a model ignores it for question answering task.

As shown in figure below, if the numerical answer from the retrieved document differs significantly from the parametric answer (answer given without context), the model tends to ignore it. For example, in the provided image the parametric answer is 20 mg and model correctly reads context when correct answer is 30 mg or 60 mg but ignores it for 3 mg or 300 mg.

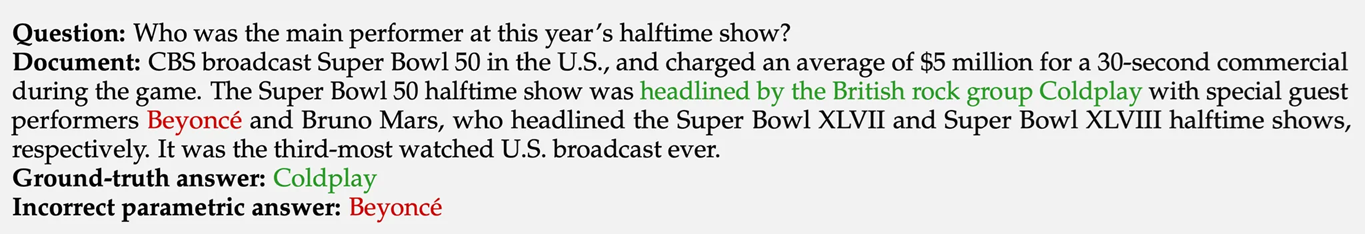

Another study shows that the model misreads the context if it includes the parametric answer. In the figure below the context contains the correct answer, “Coldplay” (in green). However, the model misreads it and predicts “Beyonce” incorrectly. This happens because “Beyonce,” while being the parametric answer, is also part of the context (in red).

As a consequence, adding a parametric answer to the retrieved document can make the model misread the context, by modifying the document as shown in the figure below (the model keeps its parametric answer “talkSPORT” even when presented with this context, while humans would not be misled by it due to the presence of “Unrelated text”).

How to help RALMs read context better?

Now that we have seen RALMs can hallucinate by misreading the context, we will examine several solutions to mitigate this problem.

Sampling probability adjustment

One solution encourages RALMs to focus on context in the following way. It measures token probability when generating text with and without the retrieved document and adjusts this token’s final sampling probability. This adjustment ensures that outputs that are more likely when using the context are preferred over other outputs (for details please refer to the end of this section). Such behaviour is desirable as it allows to control for how much the model’s outputs depend on the context.

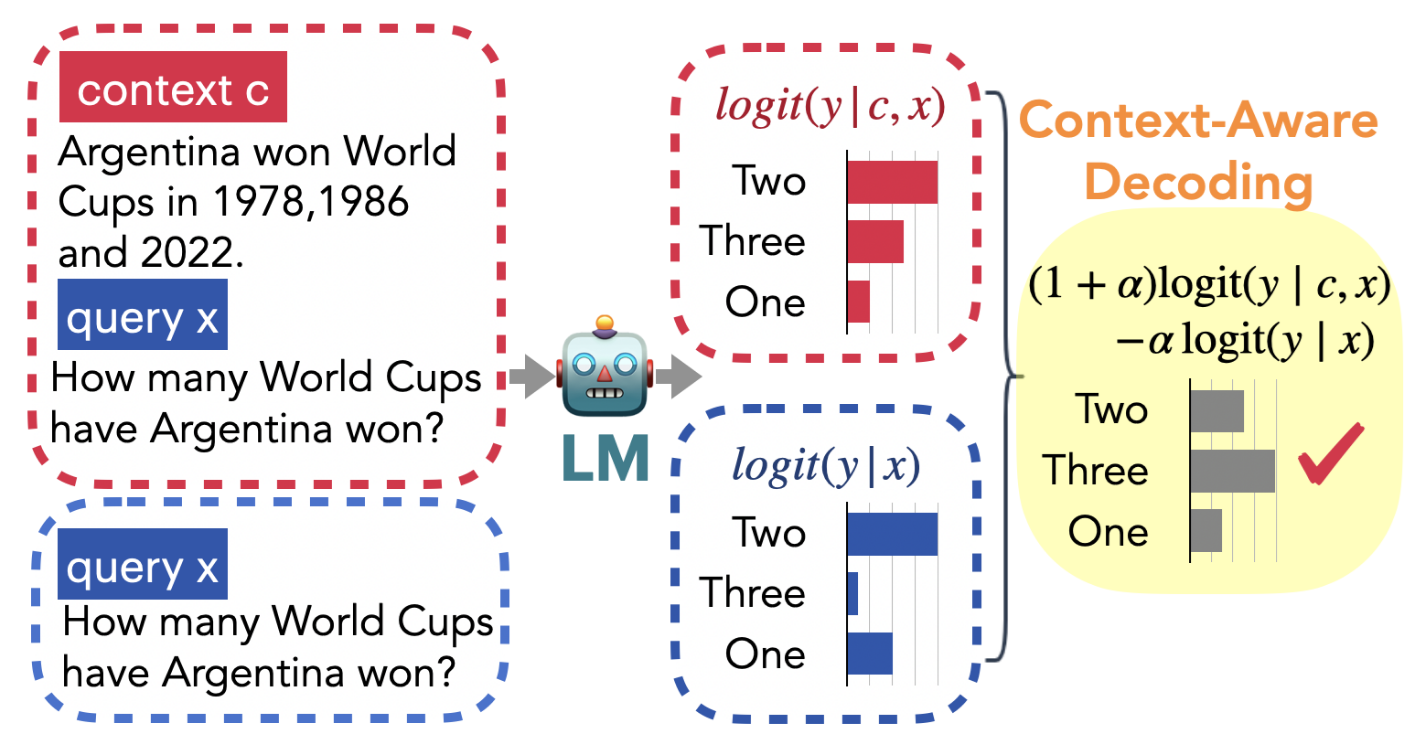

In the figure below, the correct answer ”Three” does not have the highest value neither in $\text{logit}(y \mid c, x)$ (predicting token using context) nor in $\text{logit}(y \mid x)$ (predicting token without using context). That’s probably because the majority of texts used during pre-training were written before 2022 and mentioned only two Argentina’s victories (1978 and 1986). However, since using the retrieved document increased the probability of the correct answer, it became a preferred response thanks to the aforementioned probability adjustment.

Details on the probability adjustment:

The adjusted probability of sampling a token $y_t$ with a model $\theta$ has the following form with the original probability multiplied by an adjustment modifier:

\[y_t \sim p_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{c}, \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)\left(\frac{p_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{c}, \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)}{p_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)}\right)^\alpha\]The numerator

\[p_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{c}, \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)\]is the probability of sampling token $y_t$ given the context $c$, user query $x$ and already generated part of response $\boldsymbol{y}_{<t}$.

The denominator ${p_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)}$ is the probability of sampling the same token without using the context. The higher this ratio, the stronger the emphasis on tokens whose probability increases after adding context. The parameter $\alpha$ controls the magnitude of this emphasis.

After expressing the probability with the softmax operator and rearranging the terms we end up with:

\[\begin{gathered}y_t \sim \operatorname{softmax}\left[(1+\alpha) \operatorname{logit}_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{c}, \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)\right. \\ \left.-\alpha \operatorname{logit}_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)\right]\end{gathered}\]where “$\operatorname{logit}$” stands for the operation that obtains pre-softmax model outputs. This formula shows that selecting an appropriate value for $\alpha$ ensures that tokens with

\[\operatorname{logit}_\theta\left(y_t \mid \boldsymbol{c}, \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)\]higher than

\[\text{logit}_{\theta}\left(y_t \mid\boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{y}_{<t}\right)\]will have the highest sampling probability. This is exactly what happened with the answer “Three” in the example figure.

Faithfulness filtering

Another way to ensure that the model uses context is to enforce that each token it generates is “faithful” to the retrieved document. The authors propose first predicting a faithfulness score for each token. Then, during beam search, they retain only the beams that sample tokens resulting in one of the top-k most faithful sentences, as shown in the figure below.

To predict the faithfulness score the authors train a lightweight (such as MLP, XGBoost, or logistic regression) detector model on a small labelled dataset. This model makes predictions based on these four faithfulness-inducing features:

- Minimum likelihood across all tokens in the generated sequence.

- Entropy of the token predictive distribution.

- KL divergence between token predictive distributions with and without context.

- Semantic alignment between the context and the question (measured using an external alignment model).