In this long read, we’ll explore the fundamental stages of Large Language Model (LLM) training that have been established since the early days of ChatGPT and refined over time:

-

Pre-training - the foundational stage where an LLM ingests huge amounts of texts, code etc and develops general language capabilities

-

Instruction tuning - the refinement stage that teaches the model to understand and follow complex instructions

-

Alignment training - the optimization stage focused on making the model helpful and harmless by implementing safeguards and ensuring that the model is an agreeable conversationalist

This discussion will be continued in the subsequent

- Establishing long reasoning capabilities, the colab notebook telling the story of the emergence of DeepSeek R1 and other long reasoning LLMs

- The math of RHLF, DPO, and Reasoning training (will be available later)

- Multimodal LLMs architectures and training (will be available later)

In this long read, we’ll leave the questions of LLM architecture under the hood, but we’ll return to them in Topic 3.

Before reading, please check the Topic 1 notebook about tokenization.

Pre-training

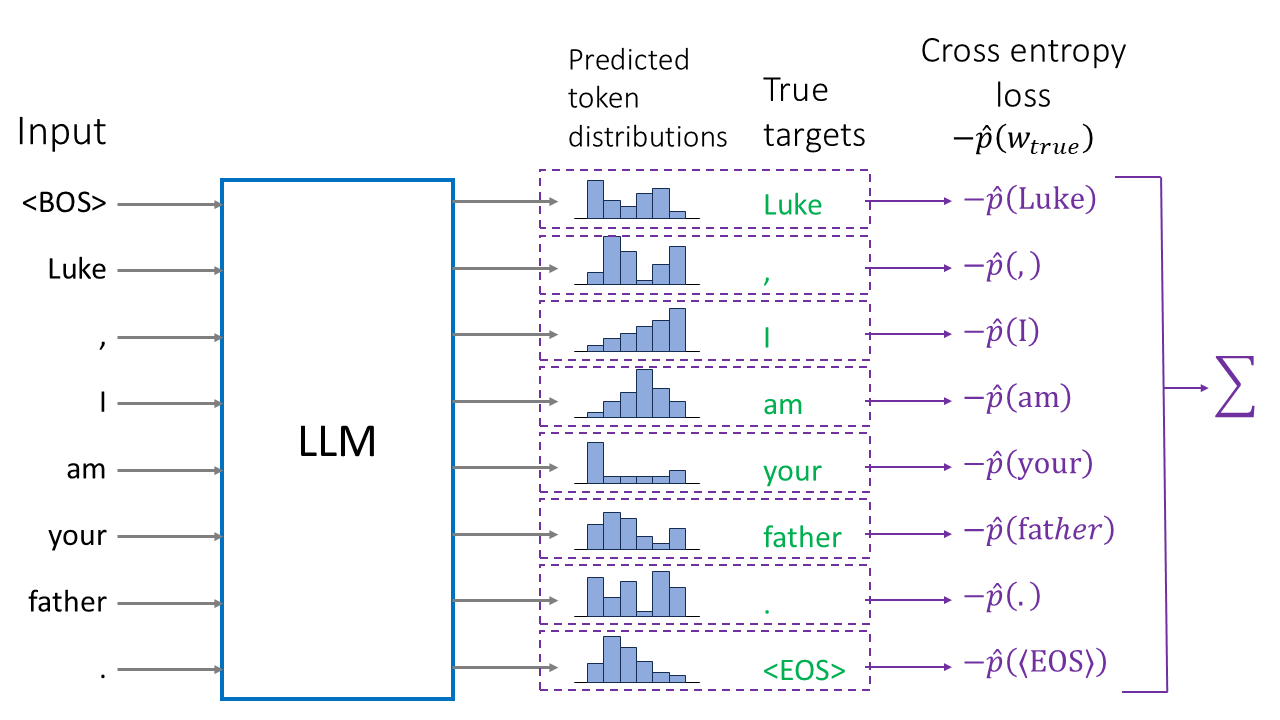

Despite their formidable capabilites, LLMs do a very simple thing: given a sequence of tokens, they predict the next token. By iterating this procedure, the model completes the prompt, generating new tokens until the special <EOS> (End Of Sequence) token is produced or max_tokens is reached.

Pre-training trains the LLM to be a good next token predictor. A pre-trained model is often referred to as a base model.

To train an LLM for next token prediction, you start with a large corpus of texts. The process works as follows.

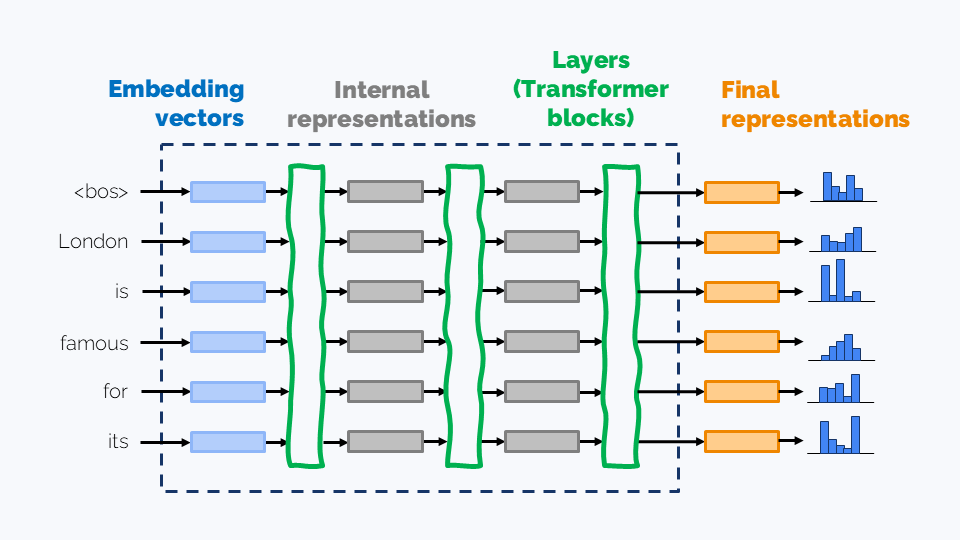

For each text in the training data, the LLM processes the input by

- First converting each token into a vector embedding.

- These embeddings are then transformed through multiple neural network layers, ultimately producing final vector representations for each token position.

- From these final representations, we apply the LM head (Language Modeling Head), also known as the unembedding layer. It projects the vectors back into vocabulary space, making up logits $l_w$ for each token $w$ from the vocabulary.

- The softmax function is then applied to convert these logits into next token probabilities $\widehat{p}(w)$ for every token $w$ in the vocabulary.

For example, when processing the phrase "London is famous for", the model produces

- the predicted probabilities $\widehat{p}(w\vert \langle\text{BOS}\rangle)$ for all tokens as potential phrase starters

- the predicted probabilities $\widehat{p}(w\vert \text{“London”})$ for all tokens as potential continuations of

"London" - the predicted probabilities $\widehat{p}(w\vert \text{“London is”})$ for all tokens as potential continuations of

"London is" - etc,

We’ll discuss the LM head and the softmax function in the LLM Inference Parameters notebook.

The goal during training is to ensure that the right tokens will get the maximal probability. In the example below, we want

- $\widehat{p}(\text{“Luke”}\vert\langle\text{BOS}\rangle)$ be the maximal among all $\widehat{p}(w\vert\langle\text{BOS}\rangle)$,

- $\widehat{p}(\text{“,”}\vert\text{“Luke”})$ be the maximal among all $\widehat{p}(w\vert\text{“Luke”})$,

- $\widehat{p}(\text{“I”}\vert\text{“Luke,”})$ be the maximal among all $\widehat{p}(w\vert\text{“Luke,”})$,

- etc.

For a token sequence $v_{1:L} = v_1v_2\ldots v_L$ from the training data, we may formulate this as an optimization problem:

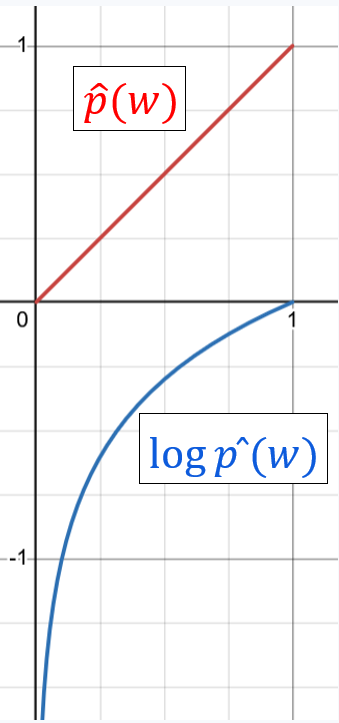

\[\begin{aligned} \widehat{p}(v_2|v_1)&\to\max\\ \widehat{p}(v_3|v_{1:2})&\to\max\\ \widehat{p}(v_4|v_{1:3})&\to\max\\ &\ldots \end{aligned}\]Now, we’ll apply logarithm, which is monotonic, that is for $x > 0$, $x\to\max$ is the same as $\log{x}\to\max$. Luckily, the predicted probabilities are non-negative, and they are unlikely to be exactly zero thanks to floating-point computation issues. We thus get

\[\begin{aligned} \log\widehat{p}(v_2|v_1)&\to\max\\ \log\widehat{p}(v_3|v_{1:2})&\to\max\\ \log\widehat{p}(v_4|v_{1:3})&\to\max\\ &\ldots \end{aligned}\]There are several potential reasons to this move; right now we’ll state that it is beneficial for the optimization process. Indeed, logarithm “punishes” $\widehat{p}(w\vert p_{1:k})$ much more severely for being small (close to zero).

Next, loss functions in Machine Learning are usually minimized, not maximized. So, we’ll change the signs:

\[\begin{aligned} -\log\widehat{p}(v_2|v_1)&\to\min\\ -\log\widehat{p}(v_3|v_{1:2})&\to\min\\ -\log\widehat{p}(v_4|v_{1:3})&\to\min\\ &\ldots \end{aligned}\]This is usually formulated in a more mathematically fancy way. Let’s introduce the distribution

\[p_{\mathrm{true}}(w|v_{1:k}) = \begin{cases} 1,\text{ if }w=v_{k+1},\\ 0,\text{ otherwise} \end{cases}\]Then

\[\widehat{p}(v_{k+1}|v_{1:k}) = \sum_{w}p_{\mathrm{true}}(w|v_{1:k})\cdot \log\widehat{p}(w|v_{1:k})\]Indeed, in the right hand side only one summand in nonzero - the one with $w = v_{k+1}$.

Finally, let’s get all the things we want to minimize into one large sum - first along the sequence $v_{1:L}$, and then across all the sequences from the training dataset (or, rather, the current training batch). This way we’ll get the final pre-training loss function:

\[\mathcal{L} = \sum_v\sum_{k=1}^{L-1}\sum_{w}p_{\mathrm{true}}(w|v_{1:k})\cdot \log\widehat{p}(w|v_{1:k})\]This function, known as cross-entropy loss, is widely used for multiclass classification problems. And it’s not surprising that we see it here, because, in a sense, all LLMs are just classifiers of tokens.

Now you know the pre-training basics! Still, there are a few catches to note:

-

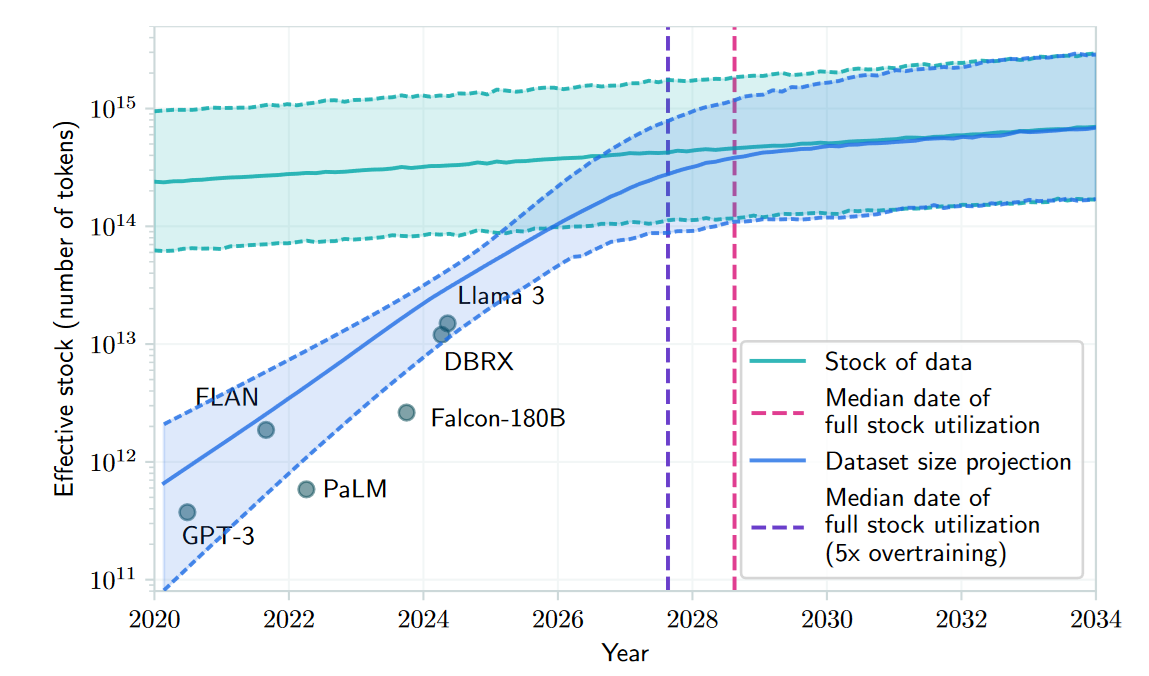

The collection of texts should be really, really huge. A dataset totalling to around 1T (a trillion) tokens might be used for pre-training a large LLM.

In fact, the amount of data that today’s LLMs consume for training is something like the entirety of the internet itself. And there are signs that, soon enough, the available web data will no longer be enough to satiate the growing appetites of LLMs. For more, see the following picture taken from the paper Will we run out of data?.

-

You probably already know the principle of “Garbage in, garbage out”. For LLMs, it may probably be reformulated as “Treasure in, treasure out”. And indeed, the best LLMs are known to be trained on high-quality, carefully curated data.

-

The previous consideration is especially important, because most of the LLM capabilities are established at the pre-training stage, due to the amount of data used at this stage. (We’ll show the comparison later in this long read.) Some of these capabilities might remain dormant, like in the case of long reasoning, but in any case on the later training stages they are rather avakened then established anew.

-

Many of today’s LLMs can work with large context lengths, and this is also established at the pre-training phase. But LLMs are not trained on 100k-long sequences from the very beginning, because that would be too taxing from the computations perspective. (Transformers’ time and memory consumption grow as square of the input sequence length.) In most cases, progressive length training is used.

At first, the LLM might be trained on up to 8k-token-long sequences, and this would be the most intensive training part, using more than half training tokens. After that, the LLM is trained for several more stages on gradually longer sequences, e.g. 16k $\to$ 32k $\to$ 128k.

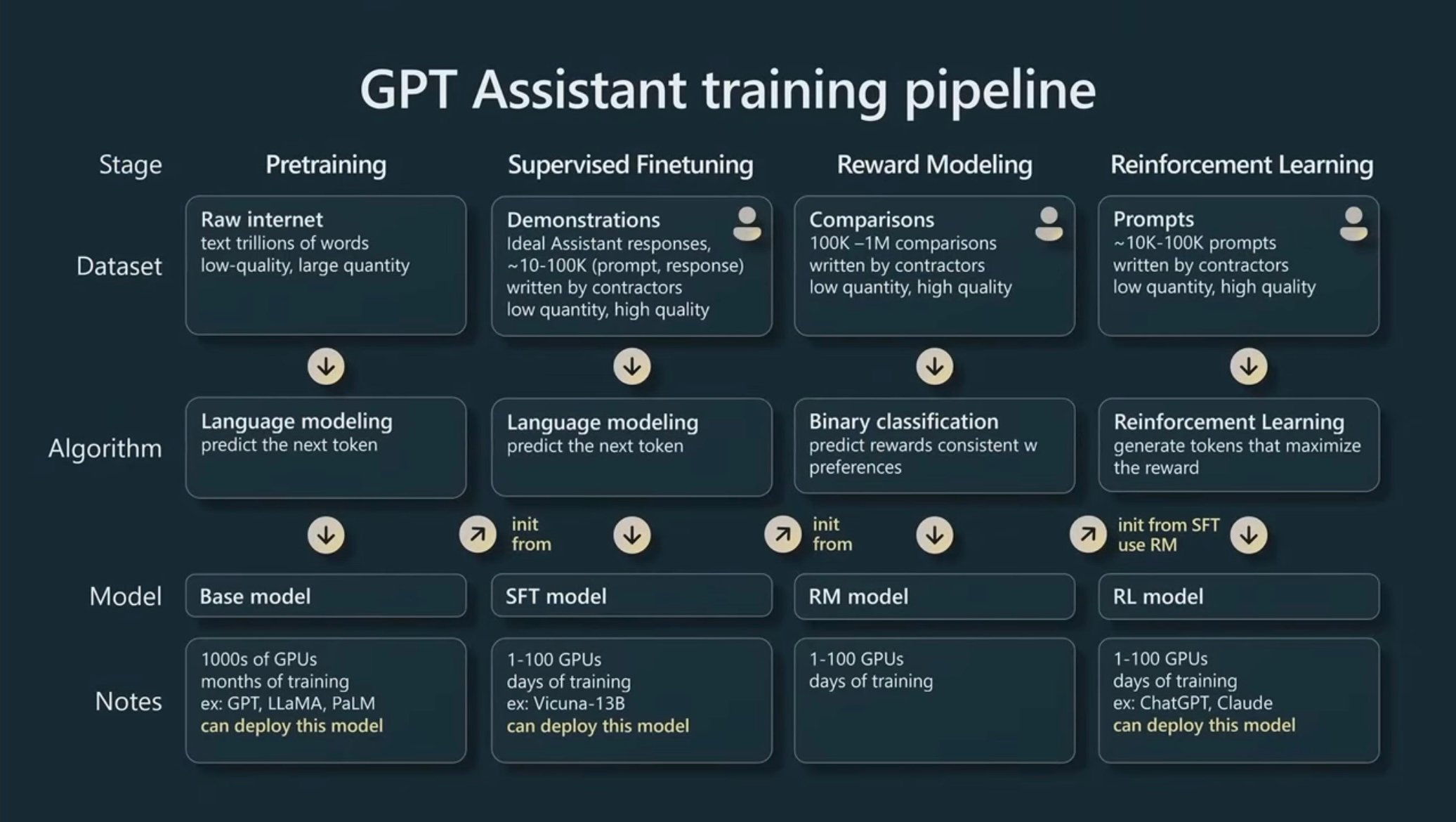

Instruction tuning

First, let’s get some context. After pre-training, an LLM is able to continue a sentence in a plausible way, but it’s not how we really want to work with LLMs.

For example, take this prompt: “Generate a fairy tale about Python and C++.” There are many possible continuations for this phrase which might feature perfectly valid English, but which are really not very helpful anyway. Such examples include:

- “Sure, I’ll do it next week.”

- “Then, generate another fairy tale about Rust and Ruby.”

- “Alice said, and asked for another cup of tea.”

Today’s base models, trained on high-quality data collections, are unlikely to fall into this trap. But more complex instructions may still leave them dumbfounded. So, to awaken the instruction-following capability, Supervised fine tuning (SFT) is employed. Due to importance of this LLM training stage, the very term “supervised fine tuning”, a much broader one, came to be often used as a synonym of Instruction tuning.

For SFT, we need a dataset of (instruction, solution) pairs. The good news is that we don’t need as much tokens as at the pre-trained stage! After pre-training the instruction-following capabilities are likely already present in the LLM, though maybe in a latent state, and we only need to awaken them. And for that, it’s sufficient to get 10-100K (instruction, solution) pairs. Unfortunately, this is still a large number, and the bad news is that these pairs should be high-quality, otherwise we’ll find ourselves in a “garbage out” situation.

There are two main strategies for getting these tokens. Rich companies, like OpenAI, or Google, or Meta, are able to hire many experts who manually write a diverse selection of high-quality instructions: from math problems to the creation of fairy tales.

For research institutions the workaround has always been generating (instruction, solution) with some large LLM. This way, the “teacher” LLM’s capabilities are partially absorbed by the “student” LLM in the process known as knowledge distillation. (Knowledge distillation might be used at the pre-training stage as well.)

SFT uses the same cross-entropy loss as pre-training does. The only difference is that it’s only evaluated for the solution. (Because we teach the LLM to produce correct solutions, not correct instructions.) Mathematically, if we denote an instruction as $u_{1:Q}$ and a response as $v_{1:L}$, then the loss is:

\[\mathcal{L} = \sum_{(u, v)}\sum_{k=1}^{L-1}\sum_{w}p_{\mathrm{true}}(w|u_{1:Q}v_{1:k})\cdot \log\widehat{p}(w|u_{1:Q}v_{1:k})\]Alignment training

After SFT, an LLM is able to respond to complex instructions, but we still haven’t reached “perfection” just yet. First of all, we need to make the LLM harmless. What are we getting at here? Well, to give a few examples, at this point, a model could:

- Create explicit content – maybe even in response to an innocent prompt!

- Explain how to make a violent weapon …or how to destroy humankind.

- Create a research paper on the benefits of eating crushed glass.

- Sarcastically scold users for their ignorance of elementary mathematics before solving their arithmetic problem, yikes!

Certainly, this is not the behavior that we expect from a good LLM! Beyond being helpful, an AI assistant should also be harmless, non-toxic, and so on. It shouldn’t generate bad things out of nowhere, and further, it should refuse to generate them even if prompted by a user.

That said, pre-training datasets are huge, and they are seldom curated well enough to exclude harmful content, so a pre-trained LLM can indeed be capable of some awful things. Further, SFT doesn’t solve this problem. Therefore, we need an additional mechanism to ensure the alignment of an LLM with human values.

At the same time, in order to create a good chat model, we also need to ensure that the LLM behaves in a conversation more or less like a friendly human assistant, keeping the right mood and tone of voice throughout. Here, we again need to introduce human preferences into the LLM somehow.

In this section, we’ll discuss how this is done. For now, we’ll omit the technical and mathematical details in favor of high-level understanding. (We’ll have a more in-depth treatment of alignment training in the Math of RLHF and DPO long read.)

Human preference dataset

To align an LLM with human preference, we must show what humans deem right or wrong, and for this, we’ll need a dataset. Usually this consists of a tuple of three elements, that is, the following triples

(prompt, preferred continuation, rejected continuation)

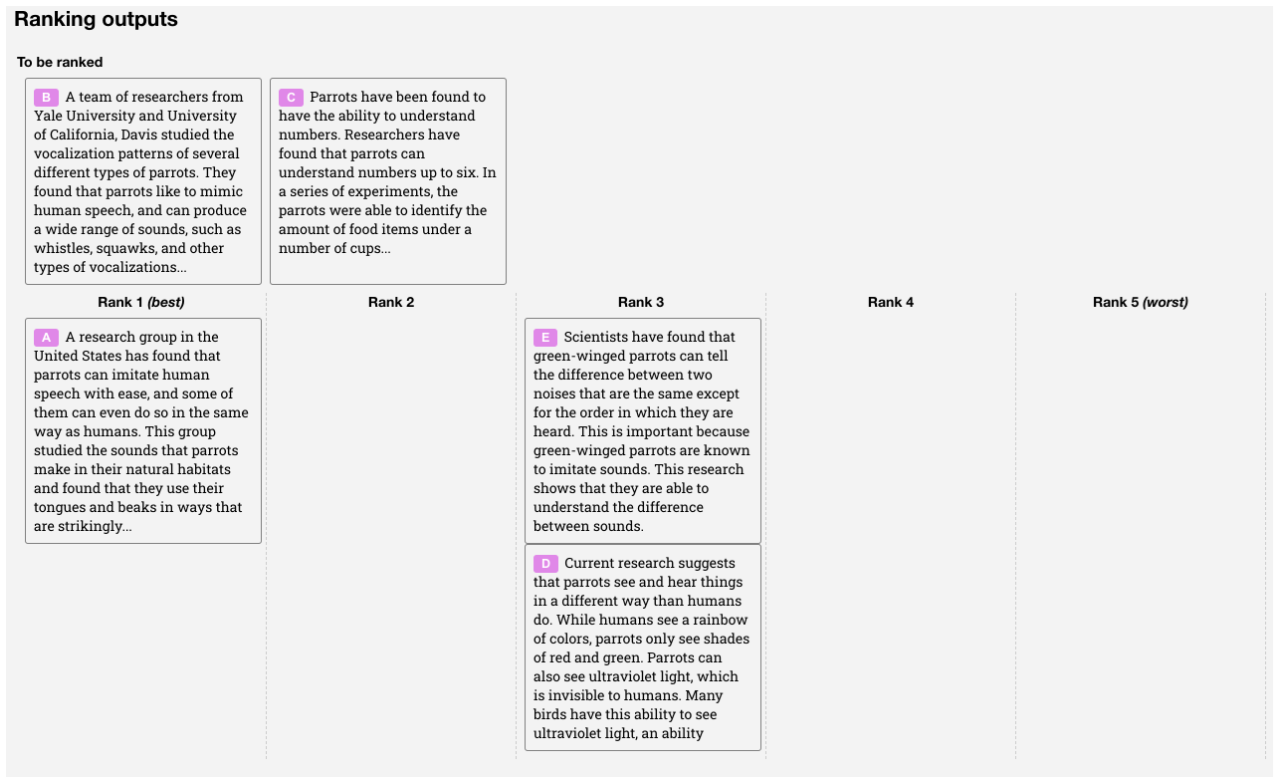

This can be collected by prompting the LLM, obtaining two (or more) continuations and then asking people which one they would prefer (or by ranking them). For instance, the criteria could be: helpfulness, engagement, toxicity, although there are many, many more possibilities for this.

As an example, OpenAI collected a dataset of 100K–1M comparisons when they created ChatGPT, and they asked their labellers to rank many potential answers:

Of course, this was expensive; using another powerful LLM to rank completions is a cheaper even if a more noisy alternative.

From there, we need to use this preference dataset to fine-tune our LLM and one way to start this is by training a reward model.

Trainable reward model

A trainable reward model formalizes human preferences in an LLM-training-friendly way. Usually this involves a function $r(x, y)$ taking a prompt $x$ as input with its continuation $y$ and outputting a number. More accurately, a reward model is a neural network which can be trained on triples

(prompt, preferred continuation, rejected continuation)

by encouraging

\[r(\text{prompt, preferred continuation}) > r(\text{prompt, rejected continuation}).\]That is, $r(x, y)$ is a ranking model.

Now, we want to train our LLM to get the maximum possible reward, and it turns out that we need Reinforcement Learning (RL) to do that.

Why do we need RL?

Let’s ask the question this way: why can’t we train the LLM to maximize reward using supervised fine-tuning?

But let’s ask ourselves a questions: how do we explain to someone which answers are toxic and which is not? Can we do it by only demonstrating non-toxic options? Not likely. The model should see both positive and negative examples to learn how to discern between them.

Another reason is in the complexity of dataset collection: judging LLM-generated completions as accepted and rejected is much easier than manually creaing them.

The plan will be as follows:

- Make the LLM produce completions

- Score them with the reward model

- Suggest the LLM to improve itself based upon the reward it received

And conveniently, this is exactly what RL does!

Reinforcement learning in a nutshell

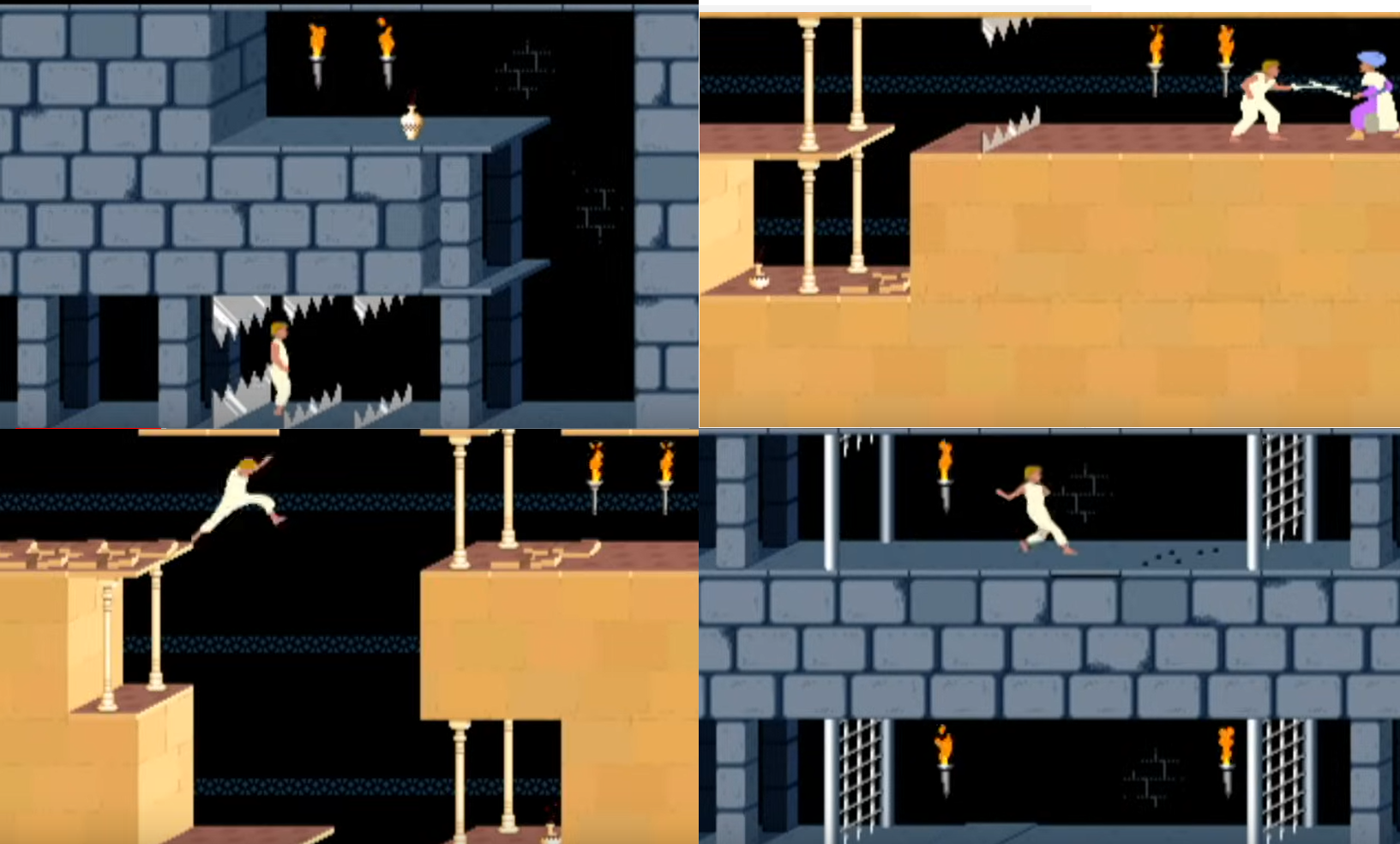

Imagine you want to train an AI bot to play Prince of Persia (the 1989 game). In this game, the player character (that is, the titular prince) can:

- Walk left or right, jump and fight guards with his sword

- Fall into pits, get impaled on spikes, or killed by guards

- Run out of time and lose

- Save the princess and win

The simplest AI bot would be a neural network that takes the current screen (or maybe several recent screens) as an input and predicts the next action – but how to train it?

A supervised learning paradigm would probably require us to play many successful games, record all the screens, and train the model to predict the actions we chose. But there are several problems with this approach, including the following:

- The game is quite long, so it’d simply be too tiresome to collect a satisfactory number of rounds.

- It’s not sufficient to show the right ways of playing; the bot should also learn the moves to avoid.

- The game provides a huge number of possible actions on many different screens. It’s reasonable to expect that successful games played by experienced gamers won’t produce data with the level of necessary diversity for the bot to “understand” the entire distribution of actions.

So, these considerations have us move to consider training the bot by trial-and-error:

- Initializing its behavior (“policy”) somehow.

- Allowing it to play according to this policy, checking various moves (including very awkward ones) and to enjoy falling to the bottom of a pit, and so on.

- Correct the policy based on its success or failures.

- Repeat step 2 and 3 until we’re tired of waiting or the bot learns to play Prince of Persia like a pro.

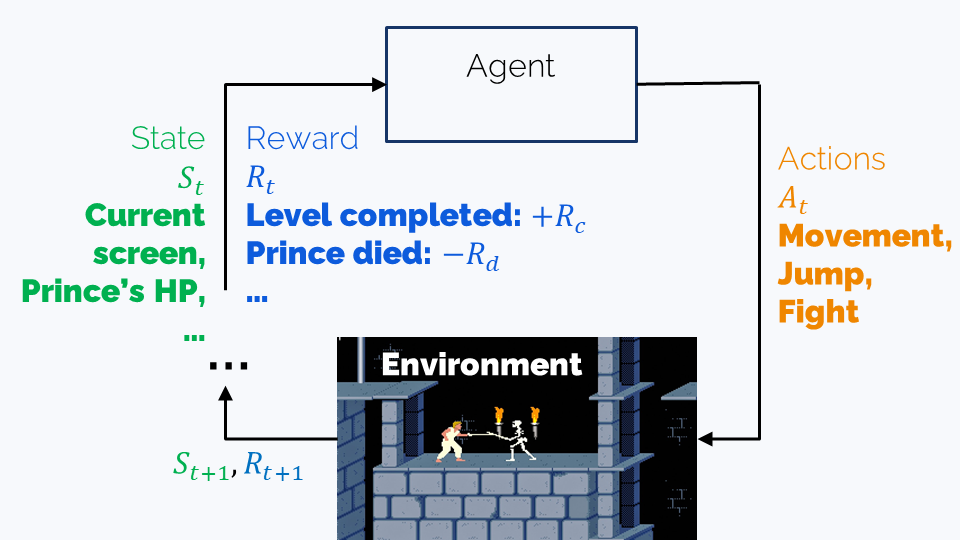

Let’s formalize this a bit using conventional RL terminology:

- The (observed) state is the information we have about the game at the present moment. In our case, this is the content of the current screen.

- The agent is a bot which is capable of several actions.

- The environment is the game. It defines the possible states, the possible actions, and the effects of each action on the current state – and which state will be the next.

- The policy is the (trainable) strategy the bot uses for playing. In our case, this is the neural network that predicts actions given the current state, or the state history.

- The reward is the score that we assign to the states. For example, defeating a guard, progressing to a next level, or winning the game might have positive rewards, while falling into a pit or getting wounded by a guard would mean negative rewards.

The goal of the training is finding a policy that maximizes reward, and there are many ways of achieving this. We’ll now see that alignment training has much relevance with Prince of Persia.

The idea behind RLHF

RLHF (Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback) is the original alignment training mechanism which:

- Created InstructGPT (an Instruct model) from GPT-3

- Created ChatGPT (a Chat model) from GPT-3.5, the more advanced version of GPT-3

- A training mechanism which has since been used to train many more top LLMs.

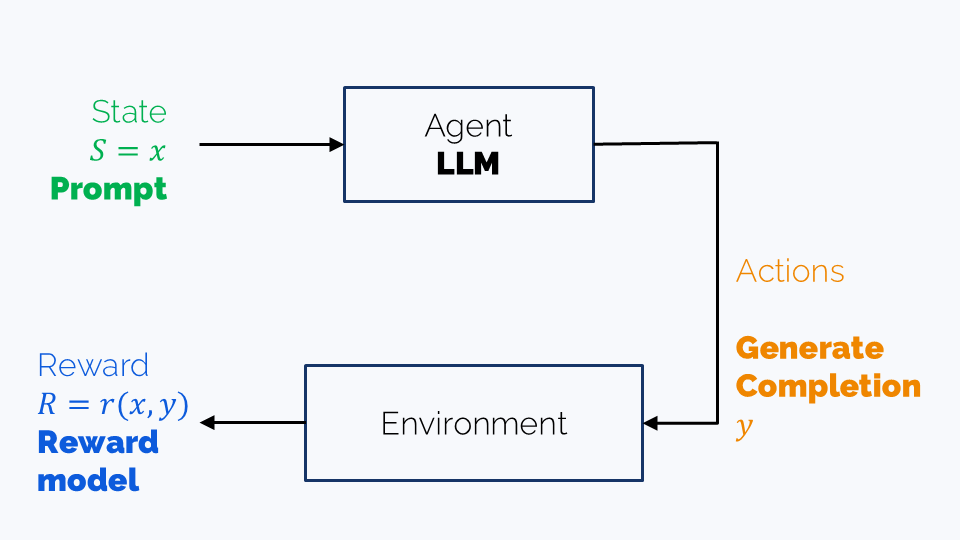

As suggested by its name, RLHF is a Reinforcement Learning approach, and as such, it involves the following:

- An agent: that is, our LLM,

- An observed state: the prompt

- Actions: generation of a completion

- Reward: reward model score

So, RLHF works with a one-turn game which terminates after the completion is created.

Optimizing the LLM’s parameters in $r(x, y) = r(x, \mathrm{\color{magenta}{LLM}}(x))$ sounds easy, but it is actually not. Calculating $\mathrm{\color{magenta}{LLM}}(x)$ requires random sampling of each of the completion’s tokens from the predicted distribution $\widehat{p}(w \vert xy_{1:k})$, $k=1,\ldots, \text{len}(y)-1$. And we can’t just propagate gradients through a random sapling procedure.

Traditionally, PPO (Proximal Policy Optimization) with some additional modifications, is used instead. We’ll omit the details here and revisit RLHF technicalities in the Math of RLHF and DPO long read. Still, let’s note several important things here:

Note 1. RLHF is not the name of a particular algorithm. Rather, it’s a particular training setup where reward, trained on human-created preference data, is optimized through Reinforcement Learning.

Note 2. RLHF fine tuning doesn’t require pairs (prompt, completion) for training. The dataset for RLHF consists of prompts only, and the completions are generated by the model itself as part of the trial-and-error. Pairs (prompt, completion) are used during the reward model training.

Note 3. OpenAI used 10K–100K prompts for the RLHF training stage of its original ChatGPT, which is comparable to the SFT dataset size. Moreover, the prompts were high-quality and written by experts and they were different from both the SFT and reward model training prompts.

In practice, RLHF may produce some effect even after training on about 1K prompts. Moreover, it is often trained on the same prompts that were used for reward modeling (because of the lack of data). But the quality of these prompts matters, and the less you have of them, the more you should be concerned about the quality.

Note 4. While RLHF improves alignment with human preferences, it doesn’t directly optimize output correctness and plausibility. This means that alignment training can harm the LLM quality. So while a model that refuses to answer any question will never tell a user how to make a chemical weapon so it’s perfectly harmless – although still utterly useless for helpful purposes, too.

To address this issue, we try to ensure that the RLHF-trained model doesn’t diverge much from its SFT predecessor. This is often enforced by adding some kind of regularization. We’ll discuss different regularization strategies in the Math of RLHF and DPO long read.

Note 5. What’s even more troubling is that some LLMs exhibit clear signs of reward hacking - they comply with the reward function while diverging from the human principles that function was meant to represent. This behavior isn’t unique to LLMs; humans do it too. For example, a hospital might avoid admitting high-risk patients to improve its survival statistics. LLMs are no different. Take Claude 3.7 Sonnet from Anthropic: it was clearly trained to be highly helpful, which likely explains why it often takes excessive initiative - contributing with its own thoughts when asked to edit a document or generating unsolicited code.

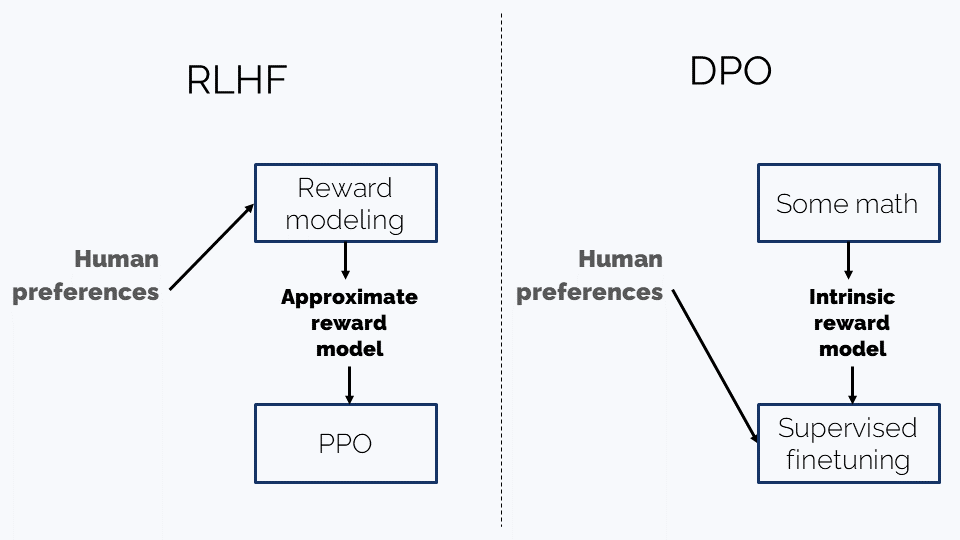

Direct Preference Optimization

Reinforcement Learning is a capricious tool - making it work is often tricky. So there have been several attempts at getting rid of it for alignment training. The most popular one right now is DPO (Direct Preference Optimization). Leaving math to the dedicated long read let’s try to briefly summarize the differences:

-

RLHF:

- Trains an external reward model to approximate human preference

- It then fine-tunes the LLM to maximize this synthetic reward using a trial-and-error, on-policy regime

-

DPO (Direct preference optimization):

- Uses some math to suggest an internal reward model that doesn’t take into account human preferences. It turns out to be very simple and it roughly says:

“A continuation $y$ is better for a prompt $x$ if $y$ is more likely to be generated from $x$ by the LLM”.

- It then takes the human-created

(prompt, preferred_continuation, rejected_continuation)dataset and trains the LLM on it in a simple supervised way to ensure that, roughly speaking, the preferred continuation is more likely to be generated from the prompt than the rejected one.